In alchemical symbolism, the wolf appears as a ravenous animal instinctuousness that devours the King. To my mind, this conveys something of the onset of madness, where we say of someone, “something is eating him up” or “something is eating at him” or “something is eating him away”.

The alchemical context suggests a surprising spiritual dimension to the theme of the werewolf. Here , it is not so much that the man becomes a wolf, as that a ravenous wolf-force psychically devours him up. The onset of madness can feel like that hellish state where one subsists halfway between human form and some other, chaotic beastly instinctiveness eating me alive. It is the sense that some ruling principle of order in the mind will not uphold, and the psyche feels like it is being ripped apart by wild and lawless impulses. Here, a young man may face the most frustrated and intense desires, and even voice the wish for release, “if only I could go mad.“

And yet in the alchemical sphere, the wolf is not a purely negative force. Metallurgically, the wolf stands for the metal antinomy, which was called the “wolf of metals” because it bonded to all the metals except gold, enabling the alchemist to separate out gold from the “scum”. These chemical operations were parables for the transformation of the soul into a more sublime state.

"Take a fierce gray wolf... where he roams almost savage with hunger. Cast to him the body of the King, and when he has devoured it, burn him entirely to ashes in a great fire. By this process the King will be liberated; and when it has been performed thrice the lion has overcome the wolf, and will find nothing more to devour in him"

— The Twelve Keys of Basil Valentine

Here, the devouring of the wolf is experienced as a necessary stage in the reduction of the psyche to the black prima materia, from which all sublime transformation might be begin. The dissolution of madness can serve as a preparatory trial for re-integration of the self on a sounder, more spiritual basis.

In ancient Greek religion, the wolf was closely associated with Apollo, whom we popularly understand to be a sun god. But Greek religion already had a sun god (Helios), and Apollo’s sun-like epithet was Phoebus (shining), which might evoke a celestial light more sublime than the sun.

While Apollo’s name carried several epithets of light, referring to his power over dreams, prophecy, music and healing, he also bore dark epithets which cannot be separated from his mysteries of light. As Loimos the giver of plagues, he could heal plagues. As Lykeios the wolf-god, he protected the shepherd’s flock from wolves.

Apollo of Delphi was as the god of clarity, dreams and prophecy. But far from having an antagonistic relationship to Dionysos the god of madness, Apollo’s powers collaborated intimately with those of DIonysos as a divine brother. On Mount Parnassos, Dionsyso kept custody of the Delphic oracle when Apollo retired to distant celestial realms in winter. Further, as Karl Kerenyi has shown in his monograph on Dionysos: Archetype of Indestructible Life, the ritual preparations of the Pythia were intimately linked to the timing and proximity of the Dionysian rites on the same mountain.

Shamanically, Apollo served as the prototypical werewolf legend in Greece, the god of lykos (wolf) whose name was punned with lux (light). He was truly the twin deity to his sister Artemis of the hunt and the wild. The juncture between his dark and light aspects was in the “wolf-light” (lykophos), the silver time just before dawn when only wolves can see, but that also heralds the shining of the dawn at first light.

In a separate monograph on Apollo, Kerenyi drew connections to Apollo as a wind god, and the prototype for the Spirit as the breath of God. These Apollonian connections with wind, wolf and the breath of spirit are drawn more sharply in Daniel Gehrenson’s Apollo the Wolf-God. There, the author explores the etymological associations between wolf and wind which survives in the fairy tale of the 3 little pigs, where the wolf “huffs and puffs and blows” the piggys’ houses away.

One must not neglect the protective warrior aspects of Apollo Lykeios. He oversaw the initiation of boys into ephebes, who in early times lived apart from the polis and trained as soldiers, enduring pastoral isolation as they scouted and fended for themselves in the wild. Apollo’s cohesive virtues inculcated sanity and independence to these young warriors so that they might learn to be a “wolf to the enemy”, yet a friend to the citizen. After this period of military initiation, the ephebe could be welcomed safely back into the polis with full civic rights and duties.

Clothed in night – Apollo had a pervasive wolfish aspect, which could paradoxically metamorphose into his swan aspects of celestial light and spititual purity. It is as if the darkest aspects of experience could serve as a crucible to reveal the celestial light. The werewolf god takes on the status of a spirit protector and a guide.

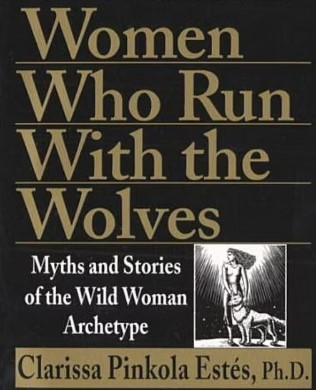

Nowhere do I find thsi more clearly grasped than In Women Who Run With Wolves, Clarissa Pinkees-Estes’ essays about the wolf-spirit as a masculine animus, a loyal companion to the wild woman archetype. The book cover art evokes the deep bond between Apollo and Artemis as brother and sister: Apollo the wolf is companion to Artemis the untamable wild Lady. Both shine with a mystery of the night, and black light.

We’ve travelled a long way from werewolf as a ravenous image of madness, to wolf-spirit and spirit-guide. I’d like to constellate a further set of references, between the wolf-spirit and a shamanic mystery of dreams.

In our popular ghost stories, the “hour of the wolf” is the darkest time of the night, when the veil between worlds is thinnest, when dreams are most vivid, and ancient supernatural fears may eat away at us, and overflow into nightmare. Blackest night is associated with demons, witchraft, death, crypts and tombs.

Yet indigenous shamanic cultures interpret this oneiric darkness much more positively. In Australian shamanic belief, there is an absolute dark. This is the space between dreams, and the adept shaman can enter into this darkness to travel from dream to dream. (Indeed, all mundane life is intimately connected to dream time).

In Kabbalah, this primordial darkness, this prima materia from which all dreams come and all nature unfolds is marked as the Shekinah, the Divine Bride of God who is “black”. She is not simply chaos, but the primal darkness pregnant with divine creative possibility. This primal darkness shines with a divine black light we cannot see.

Most recently, in Waking Up To the Dark: The Black Madonna’s Gospel for an Age of Extinction and Collapse, Clark Strand proposed that the “hour of the wolf” may indeed be the “hour of god”. Fears may enjoin the believer to pray. In Islam, this is the most sacred time for night prayers when God would most likely listen.

There is a twin mystery of the wolf and the dark. The wolf-spirit can be a guide in that darkness.

The werewolf is a terrifying nightmarish figure in our popular imagination and in our horror movies. Yet like the shaman or the alchemist, we can navigate past these thresholds of fear through sacred inner work. Then the mad figure of the werewolf may dissolve into a guardian wolf-spirit and a guide to sane spirituality.

In short, the wolf-spirit becomes a daimon.

In the white desert of New Mexico, mounds of sand roll off into the horizon. I lie among these dunes. Many illusions offer themselves. I must kill most of these, even the most beautiful, so that the true vision may come forward. Otherwise, I’d wander forever.

— from my book Questions for Werewolves

A black wolf rises upon a dune beyond me. Behind him is an absolute night. He cast his silver gaze at me.

“Wolf” is the name I give to the daimon that sees through my illusions and speaks the truth.