Wherever the Black Madonna appears in Christian traditions, she expresses a mystery that hides in plain sight, as the unseen darkness of the Holy Mary. We cannot answer “What is this mystery” in any logical way; only to allude to connections that may answer more forcefully for Her by themselves.

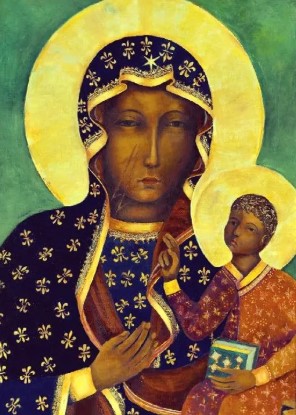

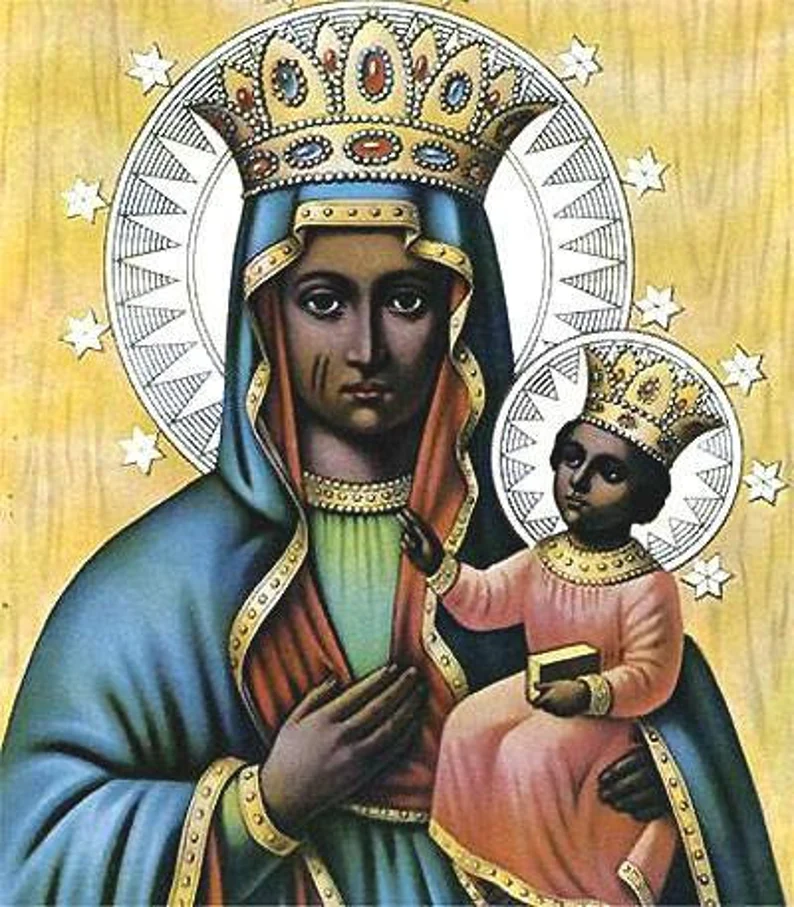

In Poland, she is Our Lady of Czestochawa, at the Black Madonna altar in the monastery of Jasna Gora. Her dark face bears three saber lines on her left cheek that may express symbolically the wounds of Christ. Her maternal woundedness symbolizes injury to the Polish motherland. She was a crucial symbol of uprising throughout Polish history and most recently in the Solidarity movement that led to the overthrow of the communist regime in 1989.

Pray

Madonna of Israel

Old Christian

Of the cypresses,

Of Lucas,

Virgin of Jasna Gora,

Black

With your face full of scars

Like the Polish Land

– Hymn to the Black Madonna by Roman Branstaetter

In the 19th century, Polish mercenaries brought figurines of the Black Madonna to Haiti , where Catholicism syncretized with African religion to create voodoo as a new indigenous religion of the americas. Here, the Black Madonna became Erzulie Dantor, and her dark face also bears three slashes on her left cheek, just like the icon in Czestochawa. Perhaps the Black Madonna expresses a darker side of the Holy Mother, in maternal suffering and fortitude. Her imagery was a deep source of inspiration for the Haiitian Revolution.

In Spain, there are 15 black madonna shrines. The most historcally important has been Our Lady of Guadalupe in the Extremdura, At this monastery, Isabelle and Ferdinand signed documents authorizing the first voyage of Christopher Columbus to the Americas in 1492.

Though the historical connections are not entirely clear, a sister black madonna vision arose in Tepeyac, in what is now Mexico City. This became Santa Maria de Guadalupe, whose iconography syncretized with the indigenous goddess Coatlicue, and has so famously travelled across Latin America. There are curious linguistic connections between the two madonnas of “Guadalupe”, as well as iconographic connections with other Marian images that sailors carried from Spain.

In Poland and Mexico, the Black Madonna became central to national Christian identity. In Haiti, but also in Europe, She expressed subversive Christian resistance. But generally, She seems to express continuity with older goddess religions apropos of the indigenous context.

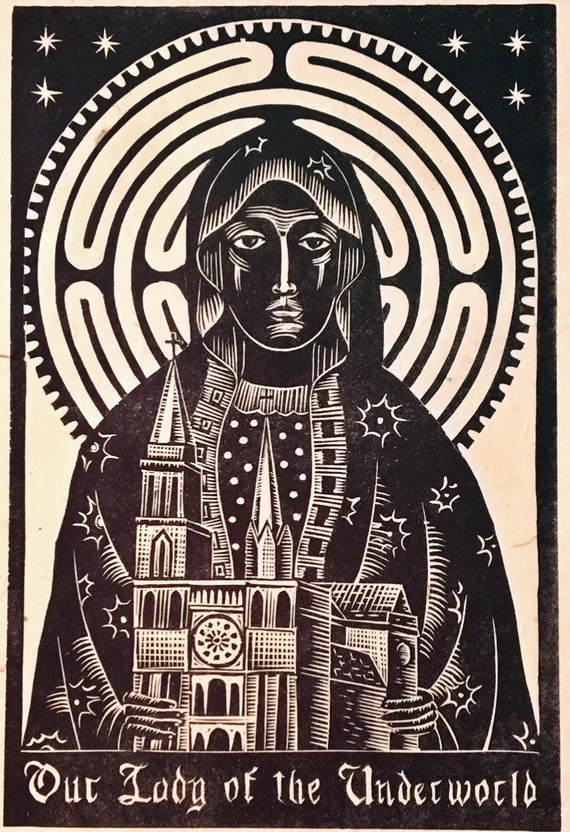

In his book Cathedral of the Balck Madonna (1988), French scholar Jean Markale was not the first to argue that Black madonna figures in Europe allowed pagan goddess traditions to survive by syncretziing with the Holy Mary. The blackened faces of these Madonnas are not accidental features of pigmentation soddened by age, but intentional features of the mystery they hide – the connections of the Holy Mary to pagan goddess traditions the new religion came to stamp out – Druidic goddess mysteries in Chartres, France; the black goddess Isis, or the dark Greek pair of Demeter and Persephone in Asia Minor. Below is a print from one of 175 representations of Mary in the Chartres cathedral just south of Paris, that evokes cross-cultural connections of the Black Madonna to the Eleusinian mysteries of Persephone, Queen of the Underworld.

The mystery of the Black Madonna hides in plain sight,everwhere in Christain churches and religious painting around the world. But all the more so in esoteric traditions within the Abrahamic traditions.

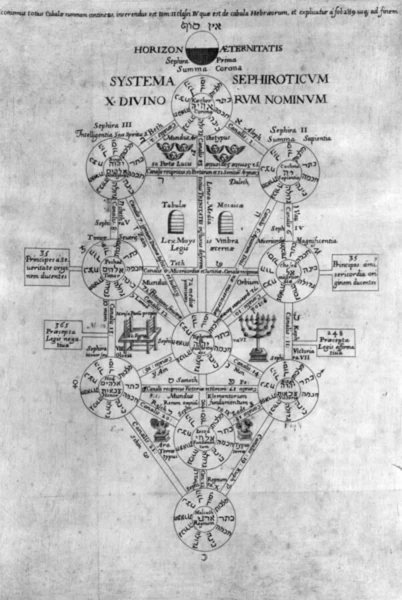

In the Talmud, the black-faced Shulamite woman in the Song of Songs has inspired Kabbaliistic commentary on the Shekinah, the Divine Bride of God. This energy is closely tied to the base of of the ten mystical sefirot that for the Tree of Life by which the energy of the world matrix harbors the ceslestial energy of God.

Within the New Testament, there does not seem at first glance to be much liturgical support for a dark madonna. But within the early gnostic traditions, more emphasis was placed on the wisdom of Mary Magdalene as the closest apostle of Jesus. Further, the notion of Sophia figured prominently in gnostic gospels as both Wisdom and the feminine spouse of God abiding in matter, but her connections to Christ were occluded in the mainstream church.

It was St. Bernard of Clairvaux, who did so much to revitalize the Cistercian order of monks and also to found the Templars, who sermonized most explicitly on the Black Madonna. Born at Fontaines, which was said to have possessed its own Black Virgin, he wrote over 280 sermons on the theme of the Song of Songs. St. Bernard spoke eloquently of the Sposa nigrada sed formosa (Song of Songs 1:5) “black but beautiful.” Like the troubadours, St, Bernard was drawing upon older Islamic Sufi traditions, of which he was well-studied, where the Beloved was symbolic as well as spiritual.

As many monks of the Franciscan and Carmelite orders brought back statuettes of the Black Madonna from the Crusades to the West, this epithet “black but beautiful” began to describe the Black Madonnas of the new cult.

The Black Madonna also shows up in Western alchemical lore as the prima materia , the black “matter” that is fertile with divine possibility, from which the Great Work to spiritualize begins.

The [notion] of the Virgin Mary, the virgo paritura of Chartres and other sites, may be this Black Stone [of the alchemists]. In any event, this was in the minds of all those who unhesitatingly depcited the mother of Jesus with a black face, therefore recycling the well-known image of the Shulamite [in the Song of Songs]... "Pay no attention to my black color, I have been burned by the sun [that is God]."

Whether it is the Holy Ghost whose shadow covered Mary or the secret fire of the alchemists, the result of the operation remain remains the same: The primal matter turns black. But this is because, when impregnated by the Spirit, it can give birth to the One who will be the Light...."

– Jean Markale, Cathedral of the Black Madonna

This alchemical symbolism was expressed in the symbol of the Rosicrucian order, the Rose-Cross, which would eventually become the basis for our “red cross” symbol of medical rescue today.

Everywhere the Black Madonna appears in Christian context, She hides her black mystery in plain sight. But the imagery of the Black Madonna does not fit comfortably within Chrisitian Trinitarian doctrine, and contrasts sharply with more authoritative pale-skinned representations of the Holy Mother.

By the Catholic doctrine of the Assumption, Mary was simply a very good mortal woman who became the vessel for the birth of Christ; and who was taken by the angels into heaven upon her death. In contrast, the Black Madonna expresses profound ambiguities with older mystical and goddess religions, both esoteric and exoteric.

As long as we don’t over-psychologize or over-fit Her into official church doctrine, this is not a spiritual problem for a Christian. Her imagery is most fertile when understood as sublimely and constructively ambiguous.

I gave up desires, as lost causes. And then She came to me – the Black Virgin beyond shape.

Beyond the door, there is no one in the dark… but Her.

You close what is open.

You open what is shut.

– from my book, Questions for Werewolves (2026)

In our troubled modern times of plague and war, of global mental sickness, of injury to the earth and to the sacred feminine, the Black Madonna speaks to us vividly, and more urgently than ever.