Why does Hollywood release horror films around Christmas time? What is the connection between horror and Christmas — which is both the day when Jesus was born, and the turning of Yule when winter light finally starts to ebb again toward Spring? There may be something expressed in the darkness of horror films, however morbidly deformed, which echoes the mystery of death and resurrection.

Robert Eggers’ commanding re-make of Nosferatu was released on Christmas Day, and it presents a picture of the vampyr as a masculine animus of sheer animosity, that haunts the soul of the wife of young Jonathan Harker. This black animus figure literally holds everyone in his grip, and all who approach him succumb to a deathly fear and paralysis, as if held hostage to the harshest nightmare. Indeed, the prelavent image of this influence is not his face, but the shadow of his hand, which reaches out in image after image —to overshadow the city, to grip the neck of women, to command others into hypnotic trance, and to usher in his final end in the arms of the young, saintly wife.

To shed light on this mythical theme of the vampyr, it may be helpful to read Nosferatu in light of the variations of its telling, in other fairy tales, as well as in the earlier films made, each masterpieces in their own way.

The first pattern that strikes me is that the plot is pretty much the exact inverse of the fairy tale of Sleeping Beauty. There, the cursed princess lies frozen in sleep, along with the entire town; while the forest becomes overgrown and suffocating. The role of the young prince is to cut through the overgrowth of the forest, and let in the sky light; his kiss awakens the sleeping princess from her cyrpt as well as all the townspeople, thereby lifting the curse. Here, the masculine animus is called upon to balance out the energy of the feminine anima, because only their conjunction can restore harmony to the land.

In Nosferatu, the saintly wife lies in bed awake, the entire town is devastated by plague. The dark king has the entire world of the psyche frozen in a plague. At the end, he arrives to “kiss” the princess, thereby lifting the curse of the plague. Here, the masculine animus diabolically freezes everything healthy in the psyche; he is an undeniable and incomprehensible force whose animosity will persist until the feminine anima submits to his embrace. This is an exact structural inversion of the well-loved fairy tale of Sleeping Beauty.

In Eggers’ adaptation, there is no “rose” to this final kiss. The dark king announces very clearly to her beforehand that he cannot love, but “only she can sate” him. In this mood, Eggers’ captures the purely negative potential of the animus to psychologically freeze a woman’s psyche in his controlling grip, especially if she cannot see clearly what he is.

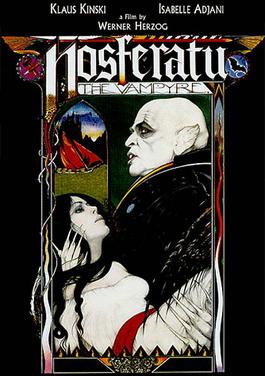

But in Werner Herzog’s adaptation, Nosferatu: the Vampyre (1979), this theme of the rose is much more clear. And the link to Sleeping Beauty is more explicit.

For a modern American audience, the film requires some patience, with its evocative quiet, its European pacing, and its almost complete absence of physical violence. But for these reasons, Herzog’s film strikes me as a more poetic experience (because the less visceral horror films are, the more poetically their mystic resonances can resound in the meditative quiet).

The contrast to Eggers’ film is striking. In the beginning, as Jonathan Harker makes his journey up the mountain to the Count’s castle, the mountains are teeming with watery life. Springs overflow, rivers course from the mountain source. It is as if something about the Count’s spirit flows inexhaustible destructible and ancient. He is indestructible life.

When Harker meets the Count, the dominant image is not the shadow of his hand, but the melancholy of his face’s white death mask. Here, in Klaus Kinski’s sensitive performance, the Count suffers from ancient melancholy, for it is worse than death to live for centuries without love, yet unable to die. Worse than death is the living tomb of the soul that endures forever without the grace of love — together with the light of spiritual resurrection that this endows.

Here, the Count evokes the figure of Hades without his queen Persephone, the maiden who returns to spring after the darkness of winter each year. He evokes Dionysos, without the resurrection of ivy and green. He evokes Apollo the dark and pestilential Giver of Plagues, without Apollo’s contrary shining power of healing plagues . And he evokes the Christ, perpetually darkened in the tomb without resurrection into the spiritual light.

Here, the plague that descends upon the town is quiet and eerily beautiful, like a melancholic’s world would be. The world is ending like in revelations, and the townspeople give up all their burdens in somber laughter, courtly dance and a final last supper.

Here, at the end, the Count reveals to the saintly wife that he yearns for a taste of true spiritual love, such as he glimpsed in her marriage. She submits to his embrace, and the sunlight finally does touch him — at which point his entire tomb-like existence is destroyed.

I allude finally to the original film by F.W. Murnau from 1922, where the manner of the Count’s death is the most haunting. Unlike in the later films by Herzog or Eggers, the Count simply dissolves in the sunlight, like a bad dream.

The dark animus as a source of pestilence dissolves in a spiritual light, through the power of the anima.